Throughout history, the arts have been indicative of beauty, human connectedness, prosperity, creativity, and freedom of expression. By stimulating the senses, emotions, and thoughts, arts can incorporate beauty into an environment, give communities a stronger sense of identity, and challenge the status quo. Given all these options, the creativity and collaboration of the arts can also be woven into the free market economy to create work and wealth. In this so-called creative economy, how do creators, public and private support networks, distributors, and buyers interact? What roles do individuals, private actors and institutions, and government play?

Framing the Creative Economy

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

The creative economy was first referenced as an independent discipline within economics in the 1960s. In 2001, John Howkins brought the term to life in his book, “The Creative Economy: How People Make Money from Ideas.” The creative economy positions itself at the intersection of economics (contributing to GDP), innovation (fostering growth and competition in traditional activities), social value (stimulating knowledge and talent), and sustainability (relying on the unlimited input of creativity and intellectual capital).

What is Considered Art?

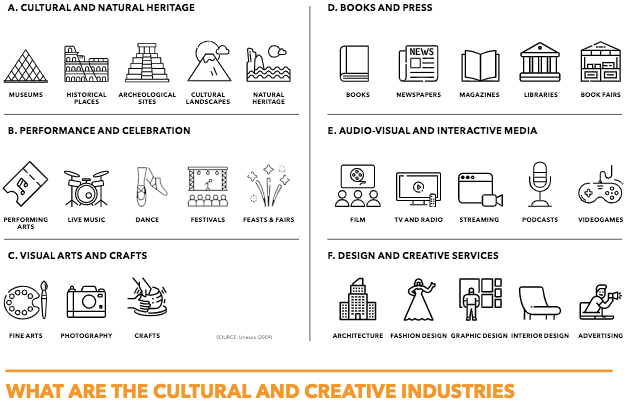

International organizations such as the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Americans for the Arts, and the World Intellectual Property Organization “have developed different criteria in an attempt to classify the creative sectors.” Industries normally considered include “those whose major outputs have symbolic values,” mainly advertising, architecture, books and newspapers/magazines, gaming and movies, music and performing arts, radio, TV, and the visual arts.

In market economies, the role of the producer is to understand what products and services are meaningful to consumers, and then find ways to create them with available resources. By taking these various industries, fueling them through creativity, and integrating them into the economy, we make “possible a level of individuality never before seen in human history.”

How Big is the Creative Economy?

The creative economy contributes just over 6.1% to global gross domestic product (GDP), averaging between 2% and 7% of national GDPs around the world. According to UN estimates, the creative economy industries generate annual revenues of over $2 trillion and account for nearly 50 million jobs worldwide. About half of these workers are women, and these industries employ more people ages 15-29 than any other sector. Television and the visual arts make up the largest industries of the creative economy in terms of revenue, while visual arts and music are the largest industries in terms of employment.

Data from the UN estimate that between 2019 and 2020, there was a $750 billion contraction in gross value added by the creative economy globally due to the pandemic. This corresponds to about 10 million job losses in the sector worldwide. For individual countries, losses in revenue in 2020 ranged from 20-40%. For more on how the coronavirus pandemic has impacted the global creative economy, see this UNESCO report.

In the U.S., employment in arts and culture generated just $446 billion in wages for over 4.6 million Americans in 2020. Additionally, economic output in creative economy sectors amounted to $877 billion, which included a $28 billion trade surplus for the export of artistic and cultural goods and services including movies and video games.

The industry saw sharp declines as a result of the pandemic. Between 2019 and 2020, the U.S. arts economy shrank at twice the rate of the economy as a whole. Over that same time period, the arts economy shed over 600,000 jobs, not counting self-employed artists. For more on the fallout from the pandemic, see this report from the National Endowment for the Arts. See your state’s creative economy profile here.

The Global Creative Economy

Countries around the world rely on the creative economy to produce jobs and growth, to stimulate innovation, to fuel tourism, and to promote culture.

U.S. Entrepreneurship

There is a particular focus on entrepreneurship in the creative economy. Between 2002 and 2012 in the U.S., the number of businesses that identified as or employed “independent artists, writers and performers,” grew by close to 40%. For example, between 2001 and 2014, self-employed musicians grew by 45% and self-employed writers grew by 20%. Artists in the U.S. are 3.6 times more likely than the rest of the U.S. workforce to be self-employed. As of May 2021, there are just over 15,000 people employed in the Independent Artists, Writers, and Performers industry, a 7% increase in employment compared to May 2020.

About one-third of Native Americans live below the poverty line, more than any other demographic group in the U.S., and the arts are an important path out of poverty for many. For self-employed artists and people who work in household enterprises, geographic isolation and lack of business experience are the biggest obstacles. Groups like We Are the Seeds, a nonprofit organization formed by Native American women, are closing this gap by providing arts education and promotional events. The Department of Interior’s Indian Arts and Crafts Board also promotes Native American economic development through the creative economy.

The European Union’s Creative Europe Program

In 2014, the European Union began its “Creative Europe” program that included 1.8 trillion euros in investment “aimed at enhancing European Cultural and Creative Industries.” This included the “Cultural and Creative Sector Guarantee Facility,” managed by the European Investment Fund, to strengthen the cultural sectors’ entrepreneurs. The plan creates a kind of public-private partnership that provides insurance to financial intermediaries like banks so as to incentivize them to finance small and medium-sized businesses in the creative economy sectors, which reportedly employ more than 12 million people in the EU. There are 5 main organizations in Italy, Spain, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom representing over 400 brands and cultural institutions that account for over 70% of the world’s market and supply almost 30 million jobs worldwide.

Canada’s Cirque du Soleil

A group of street performers in Quebec in the 1980s founded a small nonprofit and first gained government funding through a jobs-creation program. These government subsidies helped the group from 1984 to 1992, when “banks were reluctant to support the band of fire eaters, stilt walkers and clowns.” The short-term jumpstart allowed the group known as Cirque du Soleil to become the billion-dollar enterprise it is today.

Australia’s Indigenous Arts Program

Australia’s Aborigines remain the country’s most disadvantaged group, especially in terms of poverty and unemployment. Government funding as part of the Indigenous Visual Arts Industry Support Program provides about $14 million in grant opportunities for artists, art organizations, and art centers in remote indigenous communities. This government funding provided what no other sources did when Aboriginal art first gained market traction in the 1970s and today works alongside the private Aboriginal Art Association of Australia (AAAA) to provide artists with the means to create art, generate income, and develop professional skills and connections. The AAAA developed a Code of Ethics to provide a rewarding environment for Indigenous artists and includes Indigenous artists on its Board, helping to spur the Indigenous art market that is today worth close to $150 million annually.

Sweden’s Cultural Law

In 2009, Sweden declared, “Culture is to be a dynamic, challenging and independent force based on the freedom of expression. Everyone is to have the opportunity to participate in cultural life. Creativity, diversity and artistic quality are to be integral parts of society’s development.” A law based on these principles provides government arts funding, which amounted in 2016 to $220 million. Under this model, the Cultural Cooperation Model, much of the national funding is transferred to regional governments, which consult with representatives from local cultural institutions and professionals. Even though many cultural institutions such as the Swedish Film Institute and the Swedish Arts Council are government agencies, their autonomy is protected by law and safeguards exist against political intervention even in publicly-owned or financed institutions.

The Center for Art in the Middle East

The United Arab Emirates has stepped into the role of cultural center of the Middle East, hosting cultural events and making long term cultural investments. Since 2017, Abu Dhabi Department of Culture and Tourism has organized the Culture Summit, which in 2019 brought together almost 500 artists, arts administrators, media and tech leaders, and philanthropists from 90 countries to discuss technology and cultural responsibility. An agreement between governments in Abu Dhabi and Paris also allowed for a Louvre Museum in Abu Dhabi, and the UAE’s government also contributed $330 million to build the new Dubai Opera House, which is “boasting ticket sales outperforming New York’s Metropolitan Opera.”

Russia’s Cultural Controversy

There has long been a divide between public and private financing for the arts in Russia, and for many years artists have chosen to work without taking state funding. But in 2017 the fragmentation reached a new level when officials claimed a filmmaker’s production criticized and vilified the elected government. Experts say government funded projects are “likely to produce an official culture that will be stylistically homogeneous, lacking artistic freedom, and not particularly engaging,” while the “underground and counterculture will be vibrant, but neither safe nor lucrative.”

Author Tsitsi Dangarembga explains the effect of the creative economy in Africa, and why it matters to invest in it:

The Arts in Our Lives

Experiential

The arts can enhance civil society. Studies show that both audience-based participation and personal participation in the arts are linked to higher levels of civic engagement and respect for different cultures. One Norwegian study even found a correlation between participating in cultural activities and life satisfaction. This is the basis for art therapy, which has been linked to significant reductions in depression, anxiety, trauma, and distress, as well as increases in improved mood and self-esteem. Additionally, a study from the University of Arkansas investigating the impact of students taking field trips to art museums found that 70-88% of students “retained factual information from the tours” and “displayed improved critical thinking skills as well as gains in tolerance and historical empathy following the trip.”

Public Art

Public art “humanizes the built environment and invigorates public spaces” by allowing people to experience art as part of daily life. Art can give communities a stronger sense of identity; the St. Louis Arch, the giant heads of Easter Island, and the High Line in New York City are defining features and exemplify how the arts are woven into the fabric of a location. Places with dynamic cultural scenes are also attractive, adding to the community’s prosperity. Two-thirds of businesses consider the arts an important element in making communities attractive places to work.

Tourism

Beyond attracting businesses, the arts attract people. The United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) defines cultural tourism as “movements of persons for essentially cultural motivations such as study tours, performing arts and cultural tours, travel to festivals and other cultural events, visits to sites and monuments, travel to study nature, folklore or art, and pilgrimages.”

A 2018 UNWTO survey reported an average global growth rate in cultural tourism of 4-4.5% per year between 2010 and 2015, and noted overall growth in tourism was much larger for countries that highlighted cultural tourism in their marketing policy than for countries that did not (66% to 17%).

With international closures due to the pandemic, international tourism suffered steep declines in participation and revenue. By early 2022, it had not yet rebounded from pre-pandemic levels, although the recovery has begun. The number of international tourists worldwide more than doubled in January 2020 compared to January 2021.

America’s World Heritage Sites

America’s partition in the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) helps drive international tourism to the United States. UNESCO designates areas of high cultural or natural value as world heritage sites, almost like the UN’s version of a national park. The United States has 21 world heritage sites like Grand Canyon National Park and the Statue of Liberty.

These heritage sites helped make America the third most popular country for international tourism. In 2019, the US received 79 million tourists, second only to France and Spain. Domestic and international travel and tourism in the United States had a total value of $2.6 trillion in 2019 and directly supported 15 million jobs. American citizens make 93 million international trips each year, with Mexico and Canada leading the list of popular destinations.

How Does the Creative Economy Function?

Creators

When people think about industrialization in the second half of the 19th century, most do not think about art. Nevertheless, the wealth that spread throughout society and expanded the middle class also stimulated the art market. People had more time to devote to art, meaning creators had a broader field to work with when trying to understand what was meaningful to consumers and how to create meaningful art out of available resources. More open and expanded markets made possible “forms of creative individuality” never seen before in history. “The greater the size of the market, the greater the number of artistic forms that creators can earn a living from.”

This is essential, especially given that student debt tends to hit students in the arts and humanities the hardest. According to the Department of Education, 7 out of 10 of the most expensive schools are art institutions.

Distributors

In addition to being producers of their work, artists are often distributors, turning “their personal visions into material profit by reaching large numbers of eager customers.” This can empower artists as it gives them more opportunities to thrive, whether that is through technological enhancements and access to instruments and equipment, channels for distribution and marketing like Spotify, Netflix, and Etsy, or even the amount of time that people can give to creative activities today.

Artists can also turn to outside support for help distributing their work, which is the focus of Christopher Vroom. Vroom founded Artadia in 1999, a U.S.-based national nonprofit that “identifies innovative visual artists and supports them with unrestricted, merit-based financial awards and connections to a network of opportunities.” The unrestricted nature of Artadia’s grants allows artists to be independent and keep experimenting while still having the opportunity to form relationships with Artadia’s networks. Vroom also co-founded Artspace in 2011, an online marketplace to connect artists and their works to collectors and institutions.

The coronavirus pandemic has had an interesting effect on the distribution of art as live events were canceled, art organizations shut their doors, and venues navigated outdoor performances, limited schedules, attendance caps, and social distancing guidelines. Even though very few arts and cultural organizations had used webcasting prior to the pandemic, many have turned to the Internet to deliver content and “now see webcasting as a permanent part of their operations” because it allows people anywhere to access the work of regional organizations, previously known only to residents or local visitors. The Internet has been “a lifeline” for patrons, donors, and art-lovers, and streaming has expanded audiences.

Buyers

These collectors and institutions, both public and private, also serve as consumers of the creative economy. Public museums include the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Louvre in Paris, El Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid, the Capitoline Museum in Rome, the Smithsonians in Washington, D.C. and New York, and the Guggenheim in New York, Bilbao, Venice, and Abu Dhabi. These public institutions must adhere to established self-imposed standards and codes of ethics. In the U.S., for example, the Association of Art Museum Directors’ code specifically states that art sales cannot provide funds for public institutions “for purposes other than acquisitions of works of art for the collection.” Private museums have significantly more control in selling works and collections.

Additionally, although often overlooked, families play a large role. They “can either cultivate great artists or cultivate humans who appreciate art. Both are essential in a thriving society.” This is seen when private citizens invest in art. Art is known as an alternative investment, as opposed to traditional investments of stocks and bonds. Individuals can directly invest in artists, or indirectly invest in art through art investment platforms, where buyers can create and list shares for other investors to buy. Unknown artists’ works can increase in value as they expand their brand, but even the value of well-known works can increase. The value of top artworks rose by an average of 9% annually between 2000 and 2018, while the U.S. stock market rose an average of 3%. U.S. News explains how to invest in art.

The same is true for businesses. In particular, local businesses can positively connect with their communities by buying art for their workplaces, sponsoring art events in the community or offering space for events to take place, or even engaging with local artists when designing programs for their clients or employees. When people are more engaged in cultural production, they tend to offer more support. With more support, there is the opportunity for more market-based cultural production and sustainability.

Private Enterprise and Philanthropy

In the U.S., philanthropic contributions totaled close to $430 billion in 2019. Arts philanthropy specifically in the U.S. generates about $20 billion annually. Even though this is a rather small amount compared to educational, religious, and medical philanthropies, in the visual arts alone there are about 170,000 arts-related nonprofits generating close to $2 billion in economic activity annually. Individual, corporate, and foundation donors make up about 45% of the budget for nonprofit art institutions. About 12% of their income comes from private grants, as opposed to 5% coming from public grants.

The impact results in many impressive developments. Chicago’s Art on theMart is a permanent public-private partnership that features art casted on the facade of theMart, the largest privately held commercial building in the U.S. In Grand Rapids, Michigan, ArtPrize is an “independently organized international art competition” that exhibits art in parks, museums, galleries, and even vacant store fronts. Artists are awarded grants and prizes, decided upon by public vote. Civil society institutions are also a component, such as the donor conservancy that manages and funds Central Park, or the number of privately funded arts museums and festivals across the country from Michigan to Washington, D.C. to Utah.

A 2017 study looking at arts funding in the U.S. found about 2% of cultural institutions receive more than half of all contributed revenue. Organizations with annual budgets of less than $1 million comprise 90% of nonprofit cultural groups, but only receive 20-25% of funding. The fluidity and synergism of private funding allows quick and creative responsiveness to combat such discrepancies: Many funders are now working with organizations and donors at the community level. For example, the Mosaic Network and Fund in the New York Community Trust brings together arts funders and arts organization leaders in New York City in an effort to connect funders with arts practitioners and help funders understand unique challenges facing artists and cultural organizations in New York City.

Additionally, the vast majority (close to 85%) of giving comes not from large, wealthy foundations but from ordinary citizens who see the needs of their communities differently than policy makers do. This matches economic arguments that philanthropy “is part of the implicit social contract that continuously nurtures and revitalizes economic prosperity.”

A 2015 Philanthropy roundtable poll found 47% of respondents prefer philanthropy over government to solve social problems in America (32% prefer government, 21% undecided); the poll also found 43% of respondents trust charities the most to solve social problems, while 28% trust entrepreneurial companies most and only 14% trust government agencies the most. A strong majority (60%) also believe private charities are more cost effective than the government (20%). Additionally, as they answer to neither voters nor shareholders, philanthropies tend to be more innovative, efficient, flexible, varied, and personalized in endeavors to address social issues.

Countries around the world all contribute to arts and culture in their cities, both at the private and public levels. What does set the U.S. apart is levels of private funding compared to levels of public funding. The following graph breaks it down:

Philanthropy Around the World

People “acting on their own to improve what they judge to be the common good” is also a sign of a healthy democracy, and has long been “a distinguishing strength of the U.S.” This is why in some authoritarian countries, such as Russia, Iran, and China, governments have “clamped down on charities in recent years because they want the state to be the only forum for human influence.”

In 2017, the European Foundation Center (EFC) formed as a group of ten philanthropic organizations from six countries (Denmark, France, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and The Netherlands) after the realization that less government spending on arts and culture gave increased importance to the role of foundations. The EFC further developed an Arts and Culture Thematic Network, a group of cultural managers from European philanthropic organizations to discuss, share, and gather knowledge about matters that affect funders.

The Role of Government

Art is part of a community’s or culture’s collective identity, and for this reason, government is often involved. In the U.S., government involvement in the arts began as part of the New Deal with the Public Works of Art Project in 1934, through which over 3700 artists produced over 15,000 paintings, murals, prints, crafts, and sculptures for government buildings. It served as a pilot program for the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the 1935 infrastructure program that employed thousands of actors, musicians, writers, and artists, including Jackson Pollock.

The next large development came in 1963 when President Kennedy established the Advisory Council on the Arts. In September 1965, as part of the Great Society, President Johnson continued the work by signing the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities Act, creating the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). The federal effort incentivized support for the arts at the state level as well. In 1965, only 18 states had art councils or agencies; by 1975, all 50 states did. Today, as an “independent federal agency whose funding and support gives Americans the opportunity to participate in the arts, exercise their imaginations, and develop their creative capacities,” the NEA partners with local, national, public, and private agencies and organizations across the country. In 2019, the NEA distributed $155 million in grants to organizations and individuals as well as to state and regional arts agencies.

The NEA has not been without controversy. It boils down to one question: “Is it proper for the government to subsidize the arts?” Critics maintain the NEA can leave artists dependent on grant makers. Artists may then tailor their work to appeal to grant makers, as opposed to creating works that appeal to the public, the consumers of art. Some maintain, though, that artists are dependent on their patrons, whether they are public or private. A second argument is in regards to funding. Supporters claim without NEA funding, projects and artists around the country would not receive any support at all. Yet, the NEA’s budget is dwarfed by the billions contributed by individuals, corporations, and foundations. For 2021, the NEA’s budget was $167.5 million. Even with additional funding through the American Rescue Plan, this is a fraction of the $19.5 billion donated to foundations in the arts, cultures, and humanities in 2018.

Where there is little controversy, however, is in the government’s role when it comes to education and sparking interest in the arts. In 2018, 91% of people polled by Americans for the Arts agreed that the arts should be part of K-12 education, and 89% say the arts should be taught outside of the classroom in communities as well. Through this kind of support, families can learn about the creative processes and further engage in the arts. Government can additionally support the creative processes and access to the arts by making it easier to engage in the art market through exporting and importing, or by simplifying rules and regulations that dictate self-employment or permits for organizing festivals and other public art events.

Local and State Level

Local and state business laws, such as licensing laws, impact artists’ abilities to create and sell their work. Permits can also impact the ability for citizens to organize art or music festivals. For example, New Orleans requires artists to have certain licenses to sell their art in certain places. Washington state requires a business license for artists who earn a certain amount of money from their art sales. Often, these licenses are required in order for artists to be eligible to receive grants to support their work.

Across the country, collaborations between cities, business associations, and local artists are becoming more common. Cambridge, Massachusetts’s Mayor’s Arts Task Force is one such collaboration, which includes city staff, local community leaders, and members of the artist community. Similar task forces have also started in Greensboro, North Carolina and Fernley, Nevada. State Arts Councils and Agencies, including those of New Jersey and California, also offer support through sponsor programs, grant opportunities, and a network of connections for artists. Michigan’s Council for the Arts and Cultural Affairs goes even further by coordinating with Michigan’s Economic Development Corporation, ensuring citizens can enjoy “the civic, economic, and educational benefits of arts and culture.”

National Level

Besides the NEA, a number of Congressional committees play a large role in the arts. The House and Senate Appropriations Committees have jurisdiction over funding provided to the NEA, and the House and Senate Appropriations Subcommittees on Labor, Health & Human Services, and Education also have jurisdiction over funding for museum services and public broadcasting. These subcommittees also have a say in funding for Education Department programs, as do the House Education Subcommittee on Early Childhood, Elementary, and Secondary Education and the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions.

The federal government also sets laws regarding the import and export of the arts. According to the International Bar Association, the U.S. “national policy generally favours free export of cultural material and thus its legal system does not specifically regulate the export of cultural material,” with a few exceptions. In fact, in the U.S., classification as “cultural property” allows exports and imports special legal status. According to the Office of Research & Analysis of the National Endowment for the Arts, “trade in arts and cultural goods and services largely reflects the U.S. economy’s comparative advantage in ideas-based commodities.”

International Level

Outside of the U.S., USAID supports projects that use art and music to promote peace. Americans for the Arts maintains that the arts “serve as a key component in strengthening our relationships abroad through effective international exchange and economic diplomacy.” In countries such as Somalia, arts and culture provide safe outlets for stability and socialization. Art in Embassies is a U.S.-based partnership that engages over 20,000 international artists, private collectors, galleries, universities, and museums. The program features 60 exhibitions per year and over 70 permanent art collections in 200 of the State Department’s diplomatic facilities in 189 countries. This video about the collaboration between Art in Embassies, Bennington College, and the U.S. Embassy in Oslo, Norway explains more:

Engaging in the Creative Economy

In Your Community

- Do you know the artists in your community? Have you ever engaged in-person with public art professionals or artists at a local or regional event?

- Investigate art education for families and artists.Consider contacting local universities, colleges, or libraries, which often hold events or sponsor programs.

- What role can you play to spark the creative economy in your community?

- On your municipality’s website, search for “arts and culture” to find museums, collections, nonprofit organizations, and other artistic and cultural venues near you.

- Search for private events and initiatives, like ArtPrize in Grand Rapids, Michigan, that engage artists and the public.

In Your City or State

- See your state’s creative economy profile.

- What rules and regulations surround the creation, purchase, or distribution of art?

- Check to see what kind of red tape there may be. On your state or city’s website for business, check for a drop down menu or search for “licenses and permits.”

- What are the government entities at play?

- Many states have public art program grants. To see what your state offers, check for a “financing” drop down menu on your city or state’s business website. Alternatively, search or “art grants”

- What are the private organizations or institutions that are leaders in promoting access to and education for the arts?

- Many cities and states have historic commissions, trusts, or councils on the arts. Search “art council,” “historic trust,” or “cultural trust” on your state’s website.

- Investigate how your local art council stimulates economic activity around the arts in terms of attracting production, or buying and distributing.

Nationally and Internationally

- When visiting a new city or state, do you participate in the creative economy?

- Would you pay more for art from France than from Haiti? Why?

- Should your company or organization support local artists?

- The 2022 UNESCO Global Report notes that many small creative businesses face export challenges through internet, shipping logistics, and trade finance, hindering global reach.

- Ten Thousand Villages is one of many organizations that connects buyers around the world directly with artisans. They focus on using locally sourced or renewable materials; preserving indigenous legacies and cultures; and creating partnerships with communities often excluded from the global economy.

- Since 2010, the UNESCO International Fund for Cultural Diversity has provided almost $7 million in funding for nearly100 projects in over 50 developing countries to implement cultural policies and capacity building of cultural entrepreneurs by creating new cultural industry business models.

Conclusion

The effect of the creative economy on jobs, income, and GDP is easily measurable. These levels of prosperity are accompanied by the cultural revolutions, beautification, and human connectedness that can also come as a result of creativity and freedom of expression. Living in societies that are vibrant and thought-provoking benefits individuals, who in turn use their creativity and skills to benefit their communities in a cycle of positive mutual benefit. As long as individuals, private institutions, and governments take steps to empower creative and cultural work, it will continue to be “a critical driver of economic growth and development.”

This article was originally published on The Policy Circle.